Spielwiese

Schusswaffen im Paläolithikum?

(bb) Zu den am heißesten umstrittenen Problemen im Rahmen primhistorischer und nonkonformistisch-atlantologischer Forschung gehört sicherlich die Frage, ob putative, vor-holozäne Menschheitskulturen möglicherweise bereits über hoch entwickelte Technologien verfügt haben. Naturgemäß rückt dabei - neben Überlegungen zu hochseetüchigen Schiffen oder Flugmaschinen - gerade auch der martialische Bereich ins Zentrum des Interesses, sprich: die Frage, ob 'Atlantier', Lemurier & Co. eventuell bereits 'moderne' Waffen im heutigen Sinne besessen haben könnten.

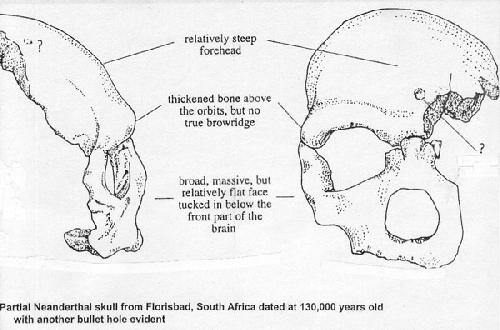

Abb. 1 Skizze des ca. 130.000 Jahre alten 'Schädels von Florisbad'. Eines von

mehreren Specimen aus dem Paleolithikum, die augenscheinlich Einschuss-

Löcher aufweisen.

In diesem Beitrag zu einem ohnehin heiklen Thema wollen wir den Komplex 'futuristischer' Hochtechnologie (Nuklearwaffen, 'Todesstrahlen' etc.) einmal beiseite lassen, und uns auf den Bereich so genannter Handfeuerwaffen konzentrieren, wie sie seit Jahrhunderten bei den 'modernen' Kulturen unseres Planeten Verwendung finden; also leichte, ein- oder zweihändig zu benutzende Schusswaffen, die mittels explosiver Substanzen (oder womöglich auch unter Nutzung anderer Mechanismen) vergleichsweise kleine Projektile mit hoher Geschwindigkeit 'abfeuern' können.

Der Alternativ-Historiker Joseph Robert Jochmans weist dazu auf das Phänomen des so genanten 'Kabwe-Schädels' (siehe dazu auch unseren Beitrag: Wer schoss auf den 'Broken Hill Man'?) hin: "Das Museum of Natural History in London stellt einen früh-paleäolithischen Schädel aus, dated at 38,000 years old, and excavated in 1921 in a cavern at Broken Hill, on the Zambezi River, in modern Zambia. On the left side of the skull is a perfect round hole 1.15 centimeters in diameter. Curiously, there are no radial split-lines around the hole or other marks that should have been left by a cold weapon, such as an arrow or spear. On the direct opposite side the skull from the hole, the cranium is shattered, and reconstruction of the fragments show that the skull was blown from the inside out—like a fatal rifle shot.

In fact, any slower projectile other than a bullet would not have produced either the neat hole or the shattering effect. Forensic experts in Germany, the United States and South Africa who have examined the Zambian skull, agree that the cranial damage could not have been caused by anything but a bullet, purposely fired at the prehistoric victim, with intent to kill.

If a high-powered weapon was indeed fired at the Broken Hill man, then one of two conclusions can be made: Either the specimen is not as old as it is claimed to be, and was shot by a European colonists or explorer within the last few centuries, or the primitive remains are as old as they are thought, and he was shot by some marksman belonging to a very ancient culture indeed. The second conclusion is by far the more plausible, especially in view of the fact that the Paleolithic skull was excavated from a depth of sixty feet, mostly of lead rock. Such a deposition of material on top of the skull was possible only over a period of several thousands of years--certainly not within the last three centuries. So the Broken Hill man, and the gunshot wound that killed him, must be dated at a very early period in prehistory. But who possessed gunpowder 38,000 years ago? Certainly not Stone Age man himself.

Jochmans verweist jedenfalls auf einen interessanten Parallel-Fund aus dem selben Großraum: "Ein weiterer menschlicher Schädel, this one from Florisbad, South Africa and dated at 130,000 years old, has both an entrance hole and an exit hole that are clean and well-defined—again, like a bullet wound.

All we can conclude is that another race of man must have existed, one far more advanced and civilized, yet who was contemporary with the Stone Age. The tantalizing question is, where was that unknown rifle-toting marksman’s home?

The National Paleontological Museum in Moscow contains the skull of an auroch, a form of extinct bison, discovered west of the Lena River and its age dates it well into the Paleolithic period. What arrested the attention of Professor Constantin Flerov, curator of the Museum, is that the forehead of the auroch was pierced by a small round hole. Like that of the Broken Hill human skull, the auroch hole has an almost polished appearance, without radial cracks. There is no doubt that the auroch was alive when its skull was shot, because calcification around the aperture is evidence of that. The animal apparently survived the shot, and died years later from natural causes. But its bones lasted through the ages, and with them evidence of the destructive ability of an unknown developed people.

One of the most controversial images found in Paleolithic art comes from the site of La Marche, recorded by French paleontologist Stephane Lwoff, and dated to 14,000 B.C.E. Among over 1,500 stone engravings is one of a mysterious figure dressed with helmet, several amulet-like necklaces, tunic and boots who is holding what looks like a rifle in one hand. The rifle is clearly shown with a long barrel, bracing bands, sight-piece, clip, cartridges and butt.

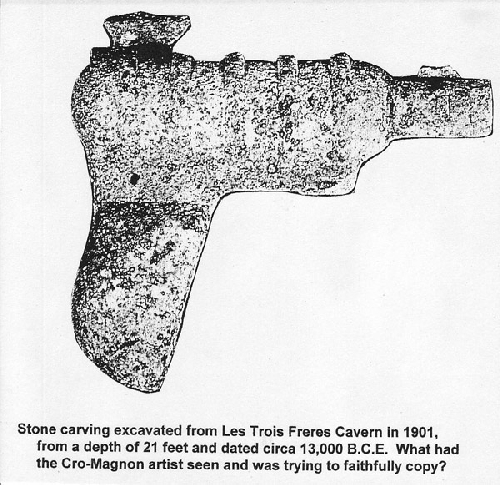

Other images appear to be of shorter barreled pistols, also shown with cartridges. In 1901, a stone carving was excavated from Les Trois Freres cavern from a depth of 21 feet and dated circa 13,000 B.C.E. It has every appearance of being a model of a pistol form of weapon, complete with short barrel, bracing bands, scope, sighting-piece and hand-held butt. What had the Cro-Magnon artist seen and was trying to faithfully copy?

Aber selbst, wenn wir 'Gewehrkolben'-Hypothese nicht folgen wollen, so